Listening to Music

Though most musicians have experience listening to music that uses instrumental and vocal techniques derived from Black American traditions—like, mostly obviously, blues, anything related to blues, jazz and hip-hop, and many more styles—they may not be used to thinking of those techniques as having a history much before the 20th century. Further, those readers who have formal musical training may be prejudiced to filter out rather than closely interpret those techniques as core expressive tools.

This section makes its point through listening examples. I invite readers to click on all sound examples and attend to them. The aim is to invite readers to take the techniques described here as part of an intricate ecosystem of expressive devices. Because some traditions of music mentioned elsewhere on this site, especially instrumental dance music of, for instance, Ignatius Sancho or Francis Johnson, require techniques already familiar to the average reader, most of what follows is drawn from recordings or settings of folk spirituals and work songs–genres that are less familiar to many types of performers active today.

*note: all recordings mentioned here but not playable can be found wherever you listen to music (Spotify, Apple Music, etc.)

1.

Singing

Adventures in tone: Heterophony

The largest type of expressive tools are variations in melody and tone color, or heterophony. (If this is a new term for you, read Open Music Theory’s straightforward explanation.) Heterophonic approaches are audible both in a single instrument/voice presentation and in groups of any variety. You will hear both mixed tone color and varied melodies simultaneously within a group.

A quick note for teachers explaining this style of music making to students: You may feel like you’re explaining against your usual set of values. If that’s uncomfortable, I simply recommend being intentional and breaking down the differences between the approaches to your students openly: sometimes we try to blend, and sometimes we try to each be distinct. Sometimes we try to make a consistent sound, and sometimes we vary our sound a lot. These are different ways that musicians make expressive musical sounds together.

Further reading: Olly Wilson’s essay, “The Heterogenous Sound Ideal in African American Music” has been anthologized in a number of places, like here.

Heterophony in Tone Quality

Hiccup

A delicate application of glottal stop, this technique may be known to you from soulful country ballads. It’s audible in almost every phrase of Hank Williams’s “Your Cheatin’ Heart.” But early recordings of Black artists suggest that, for Americans, this technique had origins in songs of enslaved singers and their descendants. In “She Brought My Breakfast,” Jim Henry “Duck” Horn hiccups at the end of the line “grey mule’s hame” [sic]. At the end of the recording, he reports to Lomax that he sang this song “in the field.”

She Brought My Breakfast

Similarly, Abraham Powell hiccups several times at the start of his “Cornfield Holler.”

Cornfield Holler

Whistling in voice, jagged register shifts

It can be quite expressive when a musician combines breathy and raspy approaches towards the top of their range; the result is something that sounds like whistling but isn’t. Instead of carrying tone across a voice’s break, many singers in these early recordings allow vocal breaks to be heard, as a kind of emphasis on melodic leaps and the words that accompany them.

Black Woman

Diamond Joe

I Got a Woman Up in the Bayou

Raspy tone

This is a kind of vocal delivery familiar from blues-style singing—applied robustly by Koko Taylor (“I Got What it Takes”) and subtly by Etta James (“I’d Rather go Blind”). To vocalists trained in a conservatory-style Euro-American approach, raspy notes might suggest a singer isn’t warmed up. I challenge you to hear raspiness instead as a tool for emphasis. Charlie Butler uses this technique to great effect in “Diamond Joe” on the words “ain’t gonna work.”

Diamond Joe

Garrison, Allen, and Ware reference “singing in the throat” in their introduction to Slave Songs of the United States, and it’s possible this technique is what they meant.

Quasi-talking

It can be quite expressive for a performer to talk in the middle of a sung performance. The temporary removal of pitch brings focus not only to the words spoken but also to the qualities of the melody when it returns. Alabama Steward blends speech and song frequently in “If she don’t come on the Big Boat.” The same is true in the more recent “I’m talking about you,” performed by Memphis Minnie.

If She Don't Come on the Big Boat

Heterophony in Ornamentation

Nineteenth-century transcribers and composers don’t record much intricate melodic variation in general—no written out turns, scoops, decorative changes in tone. Despite this lack, I suspect that a wide range of expressive tools were used with music of early to mid-nineteenth-century African Americans, just as unwritten expressive tools were often applied by performers of the music of Northern Europeans from the same period, whether in opera, parlor songs, and a variety of instrumental musics.

Examples below record simple melodic variation from the early to mid-twentieth century.

Small/large slides

Oh the Sun Done Quit Shinin

Short turns or grace notes

Oh the Sun Done Quit Shinin

Diamond Joe

Interjected exclamations

(i.e. “Oh!” or “Yea!”)

Field Holler

Can't You Line 'Em

2.

Instruments: Solo and Ensemble

Various records point to Black musicians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who were expert at a large variety of melody and harmony instruments:

I’ve provided links on this site for written music or histories of those instruments that are recent or especially rich. Many of these sources document a large variety of written repertoire played by Black musicians in the nineteenth century in particular. The material provided below is, by contrast, drawn from audio recordings and focuses on what might be called Black folk-traditions.

John Lomax and other folklorists of the early twentieth century clearly preferred voice recordings over instruments, and so we don’t have nearly the variety of sound sources for this section as above. And written evidence of instrumentalists also vastly outmatches recordings as well. But we do have some records that are instructive to the ears.

A Carolina Rice Planter, 1959. From slaveryimages.org

Banjo/Guitar

Great research has emerged recently that reveals just how integral and widespread banjo playing was among free and enslaved Black Americans of the nineteenth century. Here are three examples of picking patterns, though others are present in examples throughout this site:

John Henry

Keep Away from the Bloodstained Bandits

Thought I Heard my Banjo Say

There is a great deal more to learn about banjo design and use. I recommend consulting Kristina Gaddy’s book and extensive website, Jake Blount’s useful set of resources on Black string bands, and the American Folklife Center’s resource on Black Banjo playing.

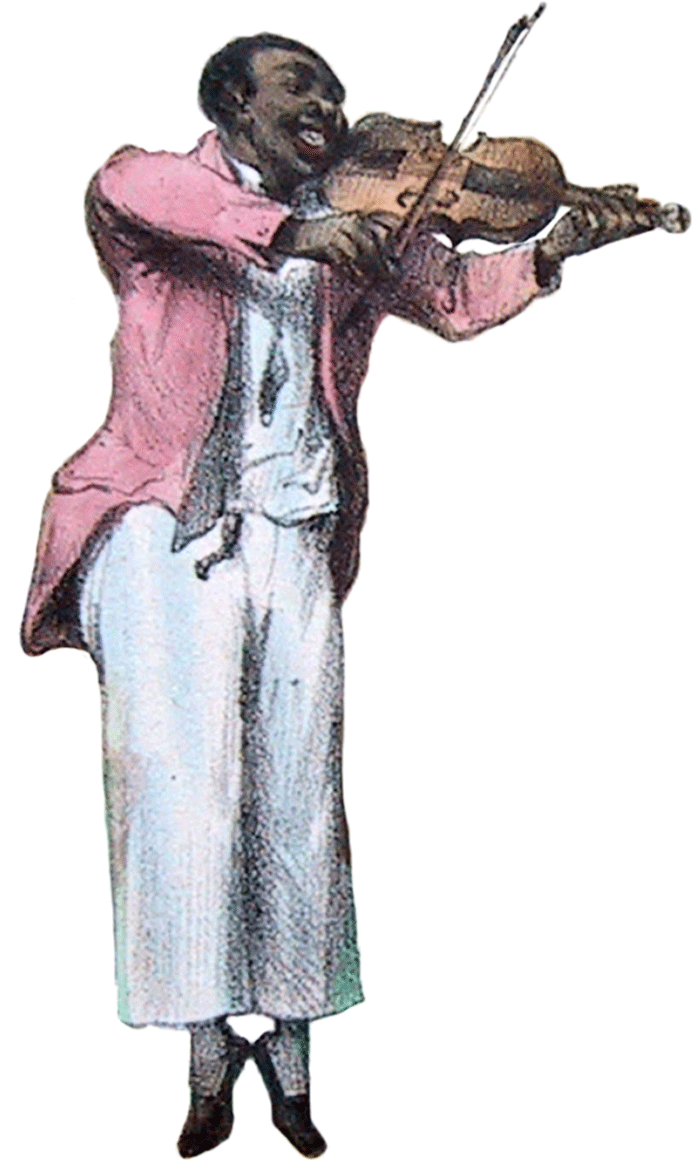

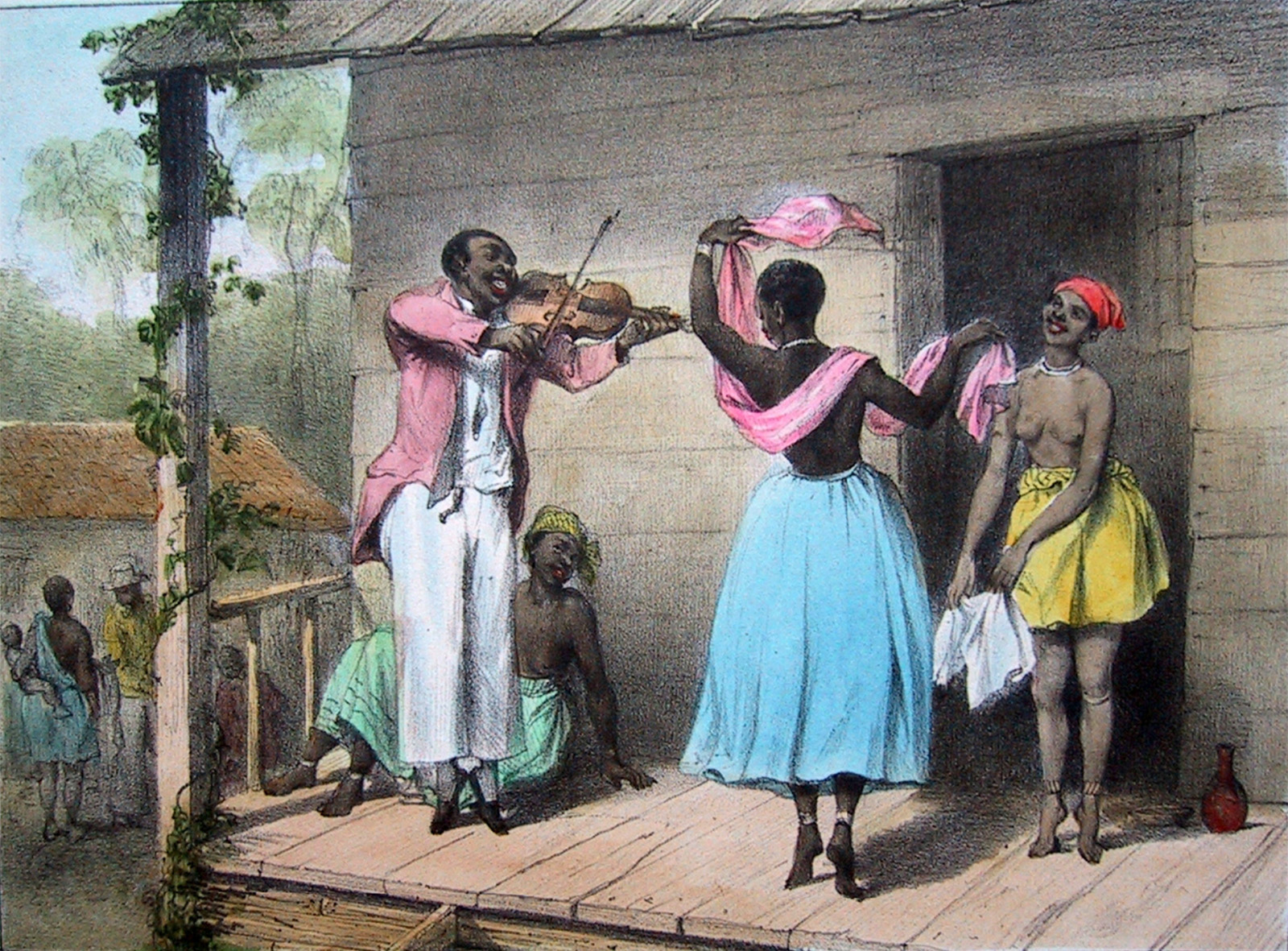

Un maître de danse créole, 1831. From slaveryimages.org

Violin

Black Americans are documented playing violins in a variety of contexts, from church to concerts and dances. Read more here in an academic article or here or here, in an online journal about Roots music.

Early and more recent recordings document a variety of techniques and repertoire, such as Andrew and Jim Baxter’s “Georgia Stomp,” recorded in 1928 and one of the earliest black string band recordings. Howard Armstrong (violin) and Ted Bogan (guitar) recorded “Love Somebody (Soldier’s Joy)” in 1989 towards the end of their careers.

Georgia Stomp

Love Somebody (Soldier's Joy)

A number of recent groups have sought to continue the Black string band tradition: Rhiannon Giddens and the Carolina Chocolate Drops began that way; The Ebony Hillbillies maintain the tradition. As above, see Jake Blount’s comprehensive page on Black stringband resources to learn more.

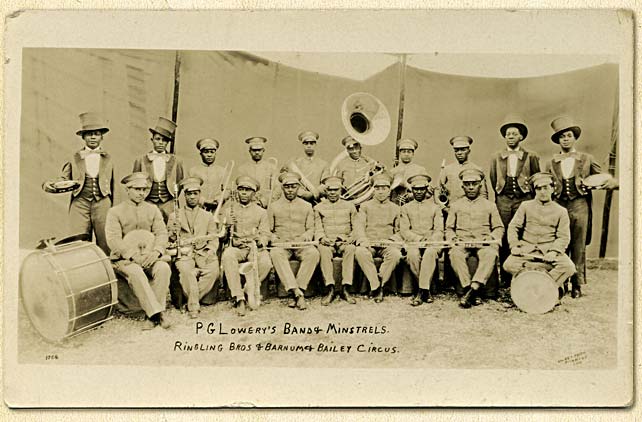

P.G. Lowery’s Band & Minstrels, Ringling Brothers & Barnum & Bailey Circus, sometime in the 1920s. Dalbey Photo, Richmond, IN. Collection of Old Hat Records

Horns/Brass

Sources like sale advertisements and runaway ads for enslaved musicians (see Freedom on the Move, Katy Ambrose’s work, as well as Eileen Southern’s work) confirm that there is a long history of Black musicians playing brass instruments on American soil. Probably the most famous Black bugle player before the Civil War was Francis Johnson of Philadelphia, pictured here with his instrument.

To find music written specifically for brass instruments by Black composers from the later nineteenth century until the later twentieth century, see Aaron Horne’s Brass Music of Black Composers. There are some modern groups who make a convincing case for revitalizing nineteenth-century brass traditions, playing nineteenth-century music on original instruments. The gallop written by Francis Johnson used elsewhere on this site is an example, because the performers, Chestnut Brass Company, play exclusively on period brass instruments.

Because of the dominance of jazz in studies of early twentieth-century Black musical life, not as much is documented about non-jazz/blues African American brass playing in the nineteenth century. There is especially a lack in early sound recordings. Johnson wrote dances and marches, which presumably were part of the repertoire of many brass bands in the mid nineteenth century. Anyone not familiar with the long history of African American marching bands or syncopated brass bands should follow up on those subjects as well.

Victoria Gallop

Jaw harp. Source: Shutterstock

Flutes/Jaw harps

By far the most simple and popular wind instrument for enslaved and free musicians would have been the jaw harp, relics of which have been found at the Mount Vernon plantation of George Washington.

Eileen Southern notes that other blown instruments were commonly made from natural materials, like “pan-pipes of cane,” depending on location and availability. For many reasons, including the lack of physical durability of these instruments as well as ethnographic bias in favor of preserving vocal practices above all else, few recordings document the use of these instruments.

This square dance recording from the Shafter camp for migrant workers in California, 1941, features jaw harp and can give you an idea of the instrument’s sound and possible use.

Drums/Percussion

This is the category that includes the most variety and also some of the most well-known and accessible instruments. Body percussion is still actively practiced and taught in many educational environments. Educators wishing to teach their students more of the history of these practices should consult Southern and Epstein, as well as the histories of juba and patting in Samuel Floyd’s essential work. Joe and Odell Thompson’s recording of “Little Brown Jug” directly references hambone. In the history of music education of young children in particular, this practice is most evident in game songs.

Little Brown Jug

Other early recordings include stomping and work sounds in regular patterns. Consider, for instance, a group of Mississippi convicts singing “Early in the Morning” and “Big Leg Rosie.” Remember while listening that many of those work songs were carried out by prisoners in a racialized incarceration system.

Early in the Morning

Big Leg Rosie

Other documented percussion instruments run the gamut: sheep ribs, cow and horse jawbones, any kind of found sticks, the bodies of instruments like banjos, and of course the human body itself. I recommend this Smithsonian Folkways recording and its liner notes to give you a sense of an overview of this wide array, as there is more history and practice than could ever be described in a single short entry.

3.

MIxED Ensembles

All of these instruments can be used in combination, especially with voice. Some ensembles play along with the vocal melody.

I Used to Work on the Tractor

Twas on a Monday

Sometimes heterophony can come in and out of focus as an expressive quality for the group. Listen closely to “My Lord What a Morning” for this effect.

My Lord What a Morning

And many readers will already know the technique of calling or interjecting over group singing, audible in “Big Leg Rosie.”

Big Leg Rosie

Further resource: From Ear to Ear, recording produced at Colonial Williamsburg, 2014.

Next: Programming »