Finding Written Music

Many of us are aware of music that carries with it the trauma and joy of Black experiences in the United States before the civil war. Arranged spirituals have become standard repertoire for choirs and corn songs for elementary students. But I want to help you find the rich array of written sources that record early Black American music making, because there is more out there—and there is always more being found.

If you’re interested in finding any kind of music written by Black composers in the nineteenth century and beyond, this site from Columbia College Chicago should be your main clearinghouse of resources. The entry on “Spiritual as Art Song” on the Carnegie Hall Timeline is also a great introduction to that particular concert genre. African American Art Song Alliance and Music by Black Composers are both useful for vocal and string music, respectively.

A number of other resources are listed at the bottom of this page. There you can find information about the repertoire of many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Black composers, ranging from those who are increasingly in the public eye, like violinist-composer Joseph Bologne and instrumentalist-composer Francis Johnson, to those who are not as widely known, like violinist Joseph Emidy and pianist Tom Wiggins.

Francis Johnson

1.

EarlY and UnPubliShed MuSic

First, of course, a caveat: Western notation and European concert music developed in tandem. So, the surviving written examples that document African diasporic music often leave out information that a modern reader has insufficient information to supply, like suitable instrumentation, how/if to repeat sections, and how/where to apply timbral, melodic, and rhythmic variation.

Further, these sources are transcribed, mostly by white individuals—and most of the transcribers were outsider listeners, sometimes enslavers, or other white people in positions of power who had neither a firm grasp of what they heard nor any experience making music in that style. Those transcribers may also have documented forced or inauthentic musical encounters that they themselves facilitated, much like when John Lomax asked Charlie Butler to “sing it louder” on recordings like “Diamond Joe.”

So, while all written musics give and reflect incomplete information, the manuscripts discussed here were produced in circumstances that should force us to be in dialogue with them on many levels. How representative of Black music making might each source be? How much of an influence did the transcriber or the context play on what was written down? These are questions for each of us to ask and to answer individually in discussion with our growing knowledge of context and history.

Now, what’s out there:

From Hans Sloane’s A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica, 1707. See also Musical Passage

The earliest notation that records African diasporic performance in the Americas comes from someone documented only as “Mr. Baptiste,” who “took the words sung” by his peers and set them to music. As Mary Caton Lingold has uncovered in her research, Baptiste was most likely a free person of color living in the Jamaican colony at the time. What survives is two pages of music, published in 1707 in a Jamaican travel narrative by Hans Sloane, who was an original founder of the British Museum in London.

`The titles here—“Angola,” “Papa,” “Koromanti”—suggest three different African or diasporic traditions, as Lingold suggests. Compared to later written examples, this music is short and may feel more like extracts, but engagement with it is no less rich an experience than with longer examples.

Over the following century, a few sources emerged here and there that are similar to the Baptiste example, particularly from the 1770s in the British Caribbean:

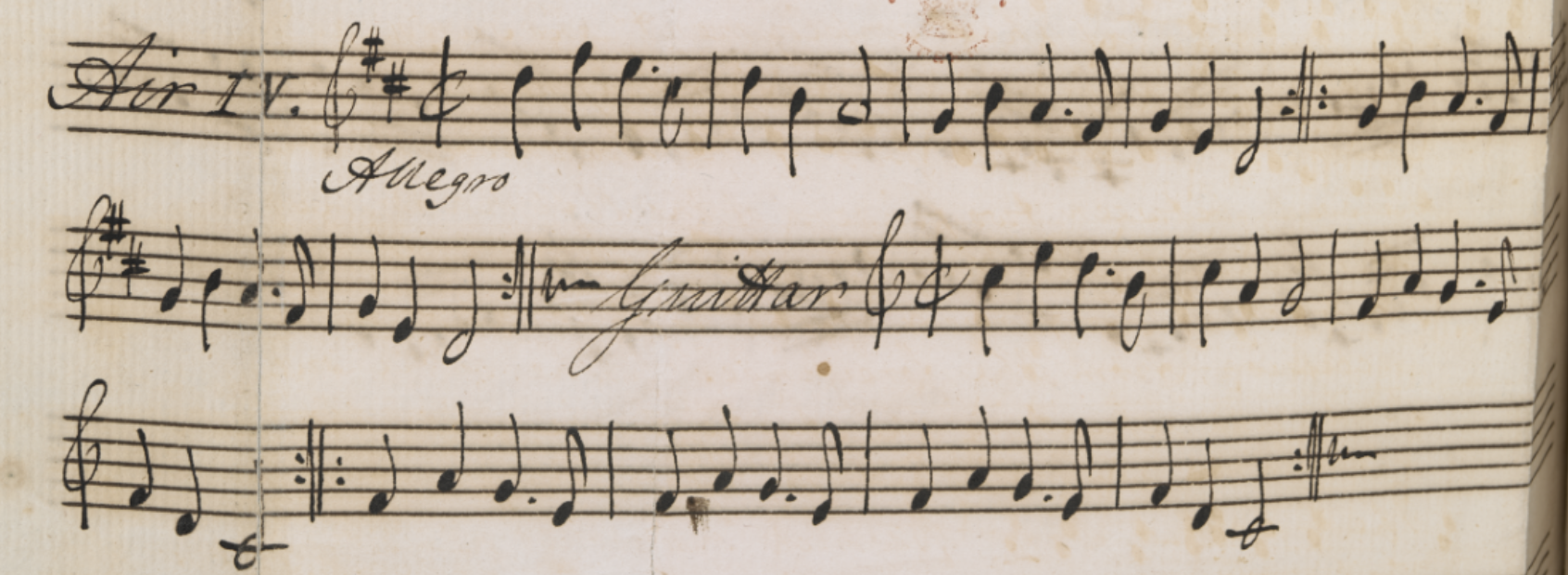

“Air IV. Golden Set. Huzza! For the golden girls”

“Jamaican Airs,” a manuscript set of songs written down to reflect musical life in the British colony, including especially popular songs, ritual dances, and performances by troupes of enslaved women or “set girls” who performed during Christmas festivities.

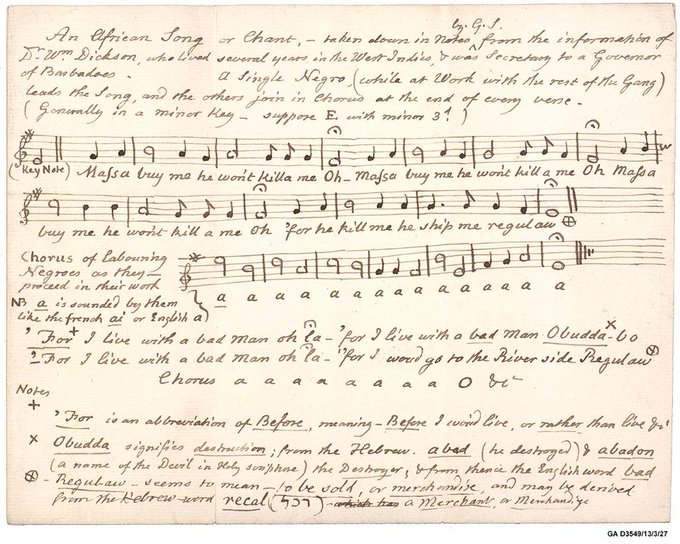

“African Chant” manuscript

“African chant,” a manuscript that includes a song sung by enslaved laborers in Barbados.

Kristina Gaddy, author of the book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History (2022), has collected several more examples of musical transcriptions from 1600-1800 on her website.

2.

NineteEnth-Century Examples and Problems

Into the nineteenth century, there are more surviving sources, and more that are notated by their Black participants or composers rather than transcribed by white observers. Interested readers should consult Eileen Southern’s anthology of readings to learn more of what’s available and more about the contexts for those examples in a depth that there is not space to explore here.

Some examples that are not widely known include:

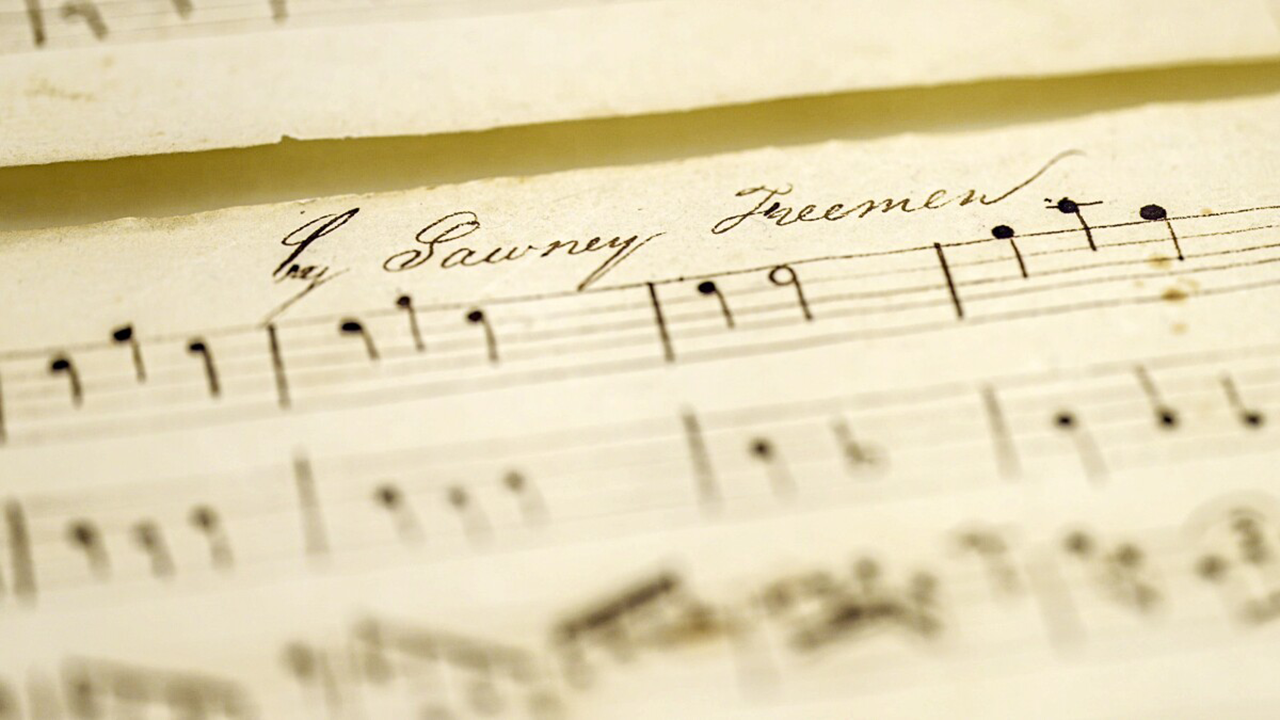

Credit: Dave Wurtzel/Connecticut Public. An 1817 manuscript of music composed by Sawney Freeman is in the archive of Trinity’s Watkinson Library

A recently uncovered collection by Sawney Freeman, a likely free Black composer in Connecticut. The series of pieces dates from Essex, Connecticut, 1817, and contains music for 1–6 instruments: dance tunes, arrangements of popular tunes, and other sorts of solo and ensemble pieces. Because this collection was only found in 2023/2024, more is sure to be learned about it and the composer. Interested readers should follow its story.

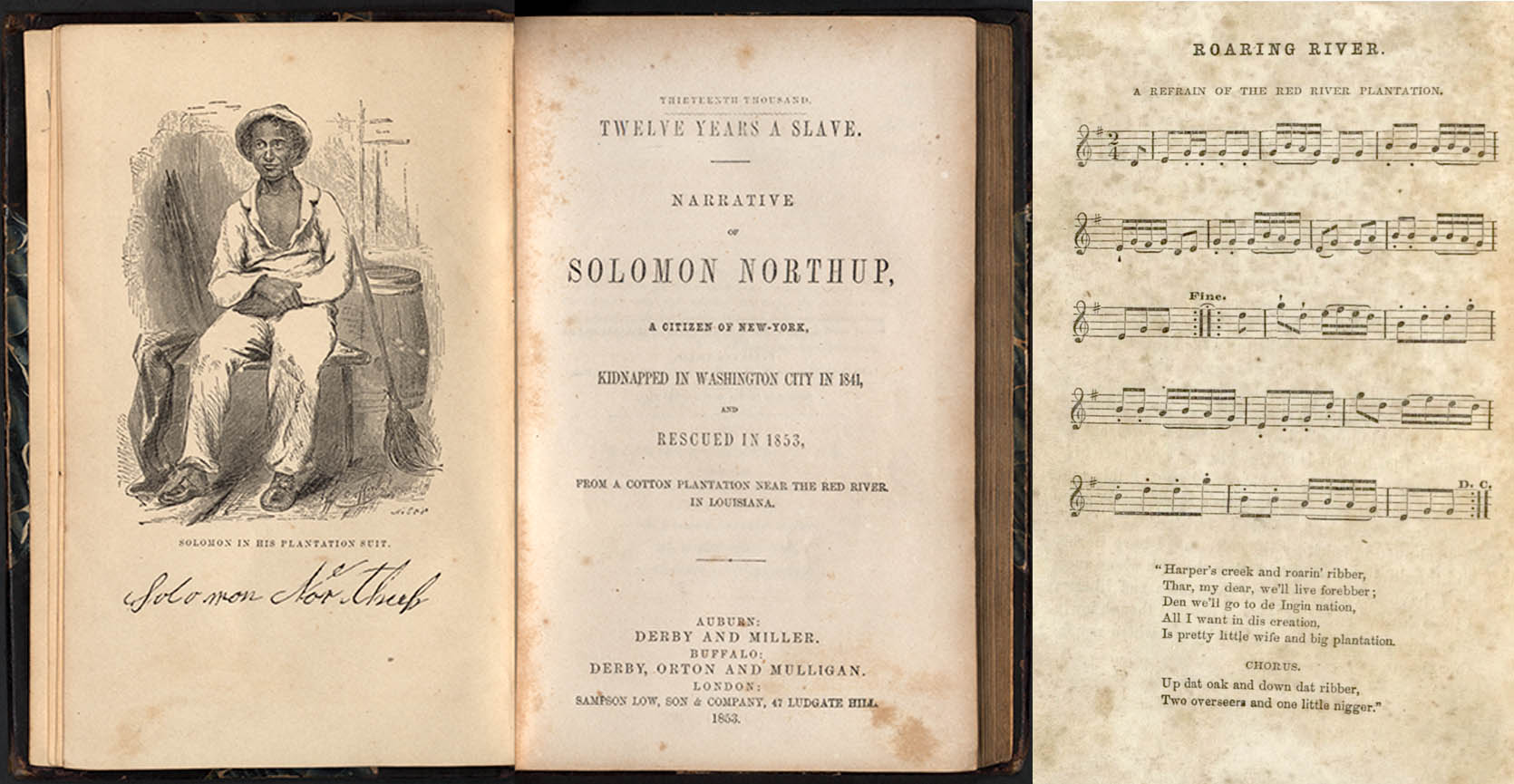

The fiddling tune published at the back of Solomon Northup’s narrative. Northup (1807?-1854) was a professional fiddler born free in New York state and illegally trafficked into slavery in Louisiana. Many will know him as the subject of 12 Years a Slave, a film named after his own memoir published in 1853. The last page of the narrative features the tune “Roaring River” that is likely to have been penned by Northup himself.

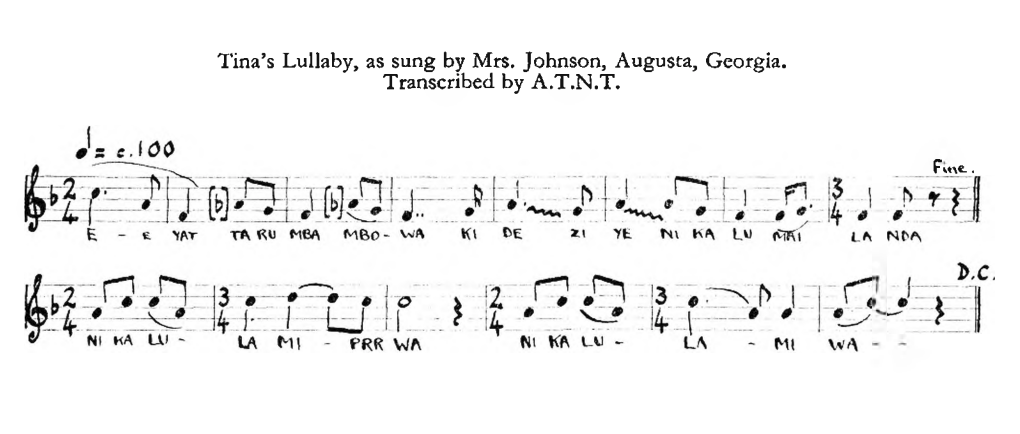

A lullaby sung by an enslaved woman named Tina, who lived in Augusta, Georgia in the 1820’s. First recorded in 1961, the song has a rich oral history described here by Mary Caton Lingold.

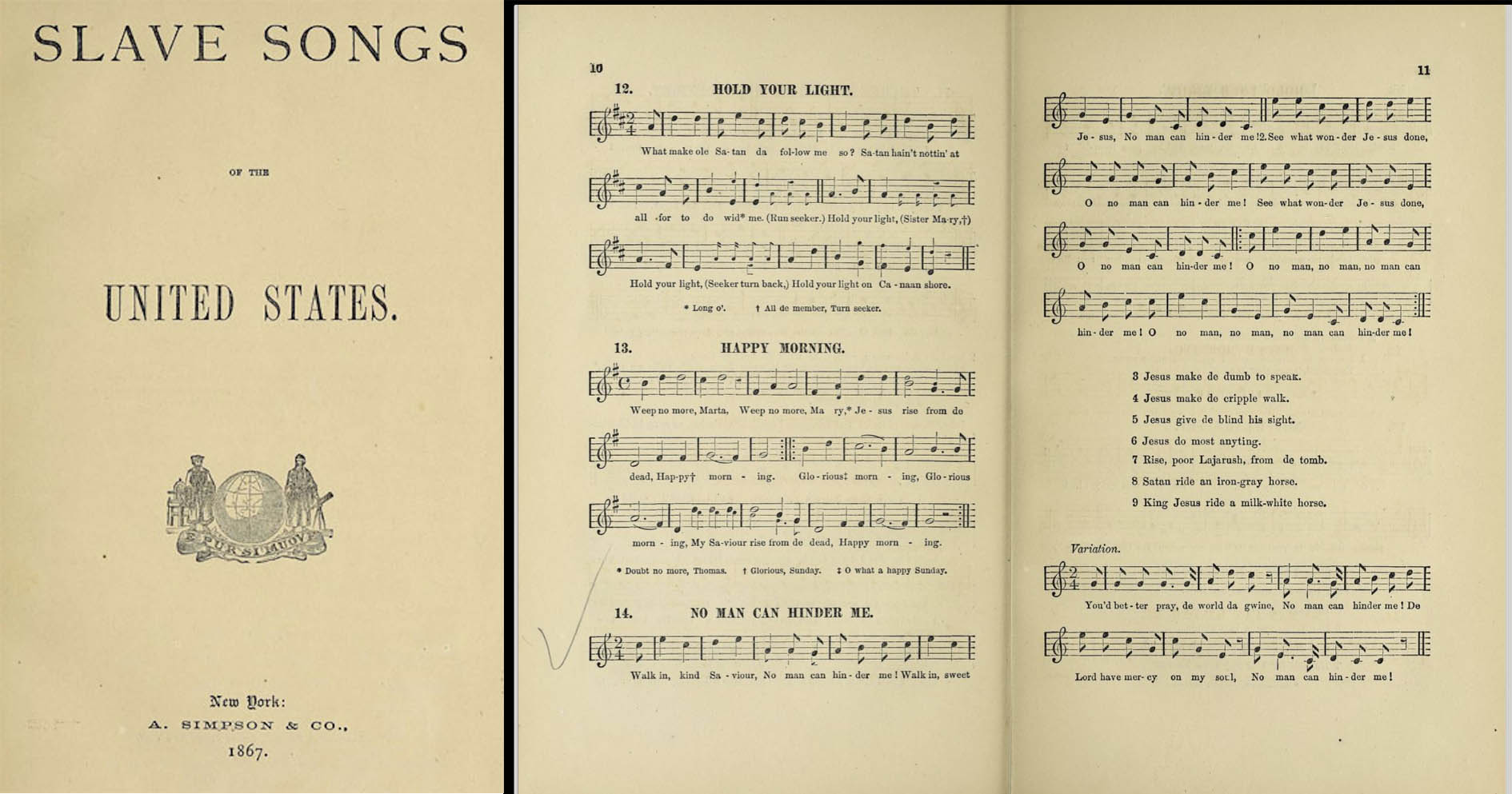

Slave Songs of the United States (1867), a book of music transcribed by the white abolitionists William Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickford Ware. The most comprehensive collection of music sung and played by un-named enslaved musicians, this book was the source for many arranged spirituals in the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is organized by geographical region, which makes it useful for those interested in exploring music from particular locales. Almost all songs are monophonic, but the introduction does a decent job of explaining the limitations of the transcribers’ methods.

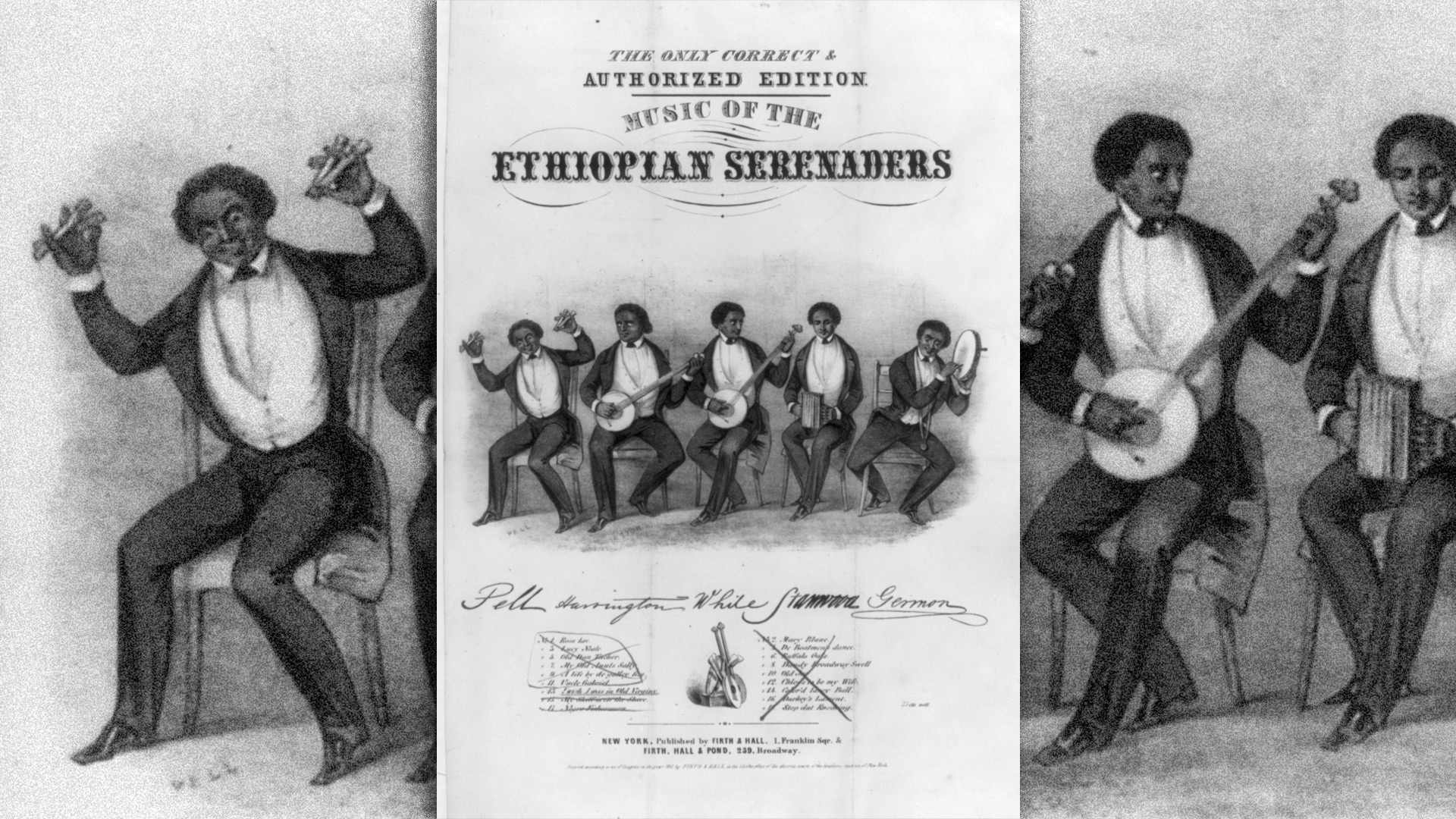

Sheet music cover art for Music of the Ethiopian Serenaders, a troupe of Blackface minstrel performers popular in the United States in the 1840s and 50s

Lastly, Blackface minstrelsy came screaming into the American stage around 1830, twisting the subjects of music, slavery, and representation in a way that should challenge performers to think carefully about almost any American popular music from the mid-nineteenth century. This performance tradition produced enormous amounts of sheet in the century that followed, some written by white performers, and some, especially towards 1900, written by Black performers. As mentioned elsewhere on this site, music of the Blackface tradition is not included here, but it is important to acknowledge its popularity and influence on a great deal of American popular music.

Next: Listening to Music »